Article: Write Up By UN Staff

A Brief History

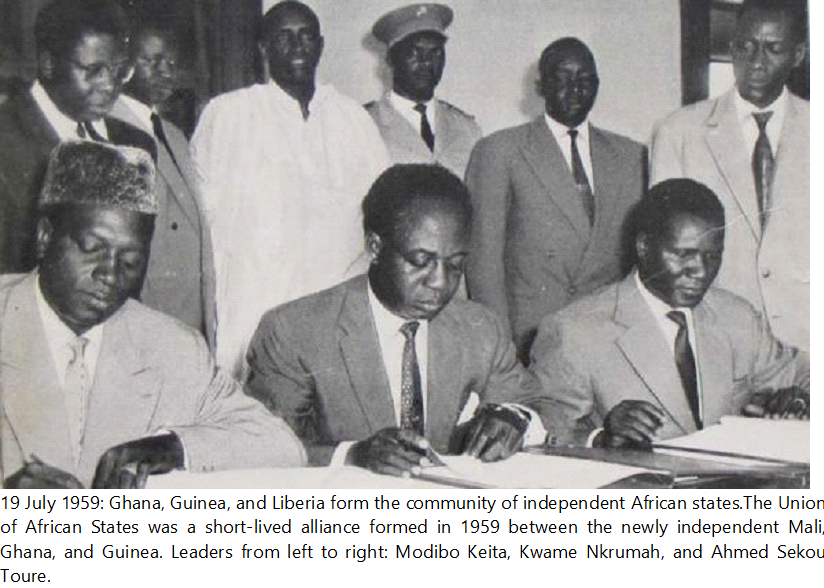

Ghana, Guinea, and Liberia were the first West African countries to achieve independence. Ghana gained independence from Great Britain on 6 March 1957, while Guinea gained independence from France on 2 October 1958. Liberia as a nation-state remained independent from western colonizers since its founding in 1847. These nations were led by Kwame Nkrumah, Ahmed Sekou Toure, and William Tubman, respectively.

Ghana, Guinea, and Liberia were the first West African countries to achieve independence. Ghana gained independence from Great Britain on 6 March 1957, while Guinea gained independence from France on 2 October 1958. Liberia as a nation-state remained independent from western colonizers since its founding in 1847. These nations were led by Kwame Nkrumah, Ahmed Sekou Toure, and William Tubman, respectively.

Years before the formation of the OAU there were attempts made by a few leaders to bring African States into some sort of a union. In 1958, for instance, a Conference of Independent African states was held in Ghana. It was not very successful. However, the alliance formed by these three nations of Ghana, Guinea, and Liberia in 1959 served as a precursor for unity within the Pan-African community on the continent. When Mali gained independence in 1960, the Union of African States was formed as a more formal group of former colonized nations. This was key in developing the Pan-African movement and philosophies of African socialism in the 1960s. These groups which were formed early in the development of independent African nations were precursors to future alliances and treaties such as the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) and the African Union (AU).

Subsequently, in 1961 another conference was held in Casablanca, led by Kwame Nkrumah, in the hope of creating a ‘common market place’ and an’ African Military command’. The Casablanca bloc wanted to form a federation of all African countries. Whereas, the Monrovia bloc led by Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal “felt that unity should be achieved gradually through economic cooperation” Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia supported that position, as well was. In the years 1960 and 1961, 12 French speaking African countries signed a Charter establishing the “Union Africaine et Malgacle”.

Road to a Unified Continent

All these attempts by the different groups signified a strong desire by African leaders of the time to form a union of some sort. However, even though all these conferences and meetings did not produce the immediate goal of a united Africa, they had one thing in common – brotherhood and solidarity among the African nations, that will eventually bring unity. One can say the signing of OAU is the middle ground that brought all the opposing sides together.

All these attempts by the different groups signified a strong desire by African leaders of the time to form a union of some sort. However, even though all these conferences and meetings did not produce the immediate goal of a united Africa, they had one thing in common – brotherhood and solidarity among the African nations, that will eventually bring unity. One can say the signing of OAU is the middle ground that brought all the opposing sides together.

Signing of the OAU Charter

Representatives of 32 African nations came to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, on May 22nd 1963, and after three days of deliberation, the founding Charter was signed on May 25th. The OAU Charter strikingly stated its ambitions and aspirations for the African nations and “peoples”. Heads of states, talked about their optimism of a reborn Africa. Haile Selassie, who was elected as the first President of the OAU, in his acceptance speech said, “Today, Africa has emerged from this dark passage. Our Armageddon is past. Africa has been reborn as a free continent and Africans have been reborn as free men.” His counterpart, Kwame Nkrumah with a stronger and bolder tone, demanded for the unity of Africa. In his speech Nkrumah said: “Our objective is African Union now. There is no time to waste. We must unite now or perish.”

Representatives of 32 African nations came to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, on May 22nd 1963, and after three days of deliberation, the founding Charter was signed on May 25th. The OAU Charter strikingly stated its ambitions and aspirations for the African nations and “peoples”. Heads of states, talked about their optimism of a reborn Africa. Haile Selassie, who was elected as the first President of the OAU, in his acceptance speech said, “Today, Africa has emerged from this dark passage. Our Armageddon is past. Africa has been reborn as a free continent and Africans have been reborn as free men.” His counterpart, Kwame Nkrumah with a stronger and bolder tone, demanded for the unity of Africa. In his speech Nkrumah said: “Our objective is African Union now. There is no time to waste. We must unite now or perish.”

An African Human Rights Doument?

Since the formation of the OAU in May 1963, Africa has been trying to construct a regional system for the promotion and protection of human rights. The idea of drafting a document establishing a human rights protection mechanism in Africa was first mooted in the early 1960’s. At the first Congress of African Jurists, held in Lagos, Nigeria in 1961, the Congress adopted the ‘Law of Lagos’ declaration calling on African governments to adopt an ‘African Convention on Human Rights’ with a court and a commission. Africa was not ready then.

Since the formation of the OAU in May 1963, Africa has been trying to construct a regional system for the promotion and protection of human rights. The idea of drafting a document establishing a human rights protection mechanism in Africa was first mooted in the early 1960’s. At the first Congress of African Jurists, held in Lagos, Nigeria in 1961, the Congress adopted the ‘Law of Lagos’ declaration calling on African governments to adopt an ‘African Convention on Human Rights’ with a court and a commission. Africa was not ready then.

In 1967, a Conference of Francophone African Jurists was held in Dakar, Senegal. Delegates, building on the idea of the Lagos Declaration, brought up the idea of a regional human rights document. Participants adopted the Dakar Declaration, and also requested the International Commission of Jurists to assist in creating a regional human rights mechanism in Africa. The UN also waded in. A series of side meetings at the during General Assembly discussions encouraged African Heads of State to set up a human rights mechanism for the continent.

Led by President Dauda Jawara, participants at one of the conferences decided to set up a mapping exercise as to what is needed and how it will be funded. Convinced that Africa does need a human rights framework, President Léopold Sédar Senghor, decided to table the proposition before the OAU Assembly at its next session. The Assembly of Heads of States and Government of the OAU meeting in Monrovia, Liberia, during the 16th Annual Summit in July 1979, instructed the OAU Secretary General to convene a committee of African experts, with the assistance of the International Commission of Jurists, to draft a regional human rights instrument for Africa, similar to the European and Inter-American human rights conventions. The then Chairman of the OAU, President William Tolbert, urged other Heads of State to support the establishment of some sort of human rights regime.

Extracts of the OAU Assembly’s Decision

AHG/Dec.115 (XVI) Rev. 1 1979

The Assembly reaffirms the need for better international cooperation, respect for fundamental human rights and peoples’ rights and in particular the right to development … The Assembly calls on the Secretary-General to:

Organise as soon as possible, in an African capital, a restricted meeting of highly qualified experts to prepare a preliminary draft of an “African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights” providing inter alia for the establishment of bodies to promote and protect human and peoples’ rights.

In 1979, twenty African experts presided over by Judge Kéba M’baye met in Dakar, Senegal. The main item on the agenda was to discuss in detail what an African human rights regime will entail and to produce a first draft of a human rights charter. The Expert Committee, under the guidance of President Senghor Sedar, and after three days of intense deliberations came up with the first draft of the African Charter.

But this was the early 1980’s. It is important to understand that in 1963 when the OAU was conceived, it was from within the cauldron of the yoke of colonialism. Understandably, the new states guarded their newfound freedom and sovereign independence jealously. The principles of sovereign equality and non-interference (the reserve domain) came to define the organisation and its members. This point was made clear in both the Algiers and Durban Declarations where the OAU eulogised its achievements of pan-Africanism in breaking “colonial yoke and regaining its freedom…” That ‘freedom’ meant a rigid application of the principles of non-interference. It also meant upholding human rights was frowned upon. Guinean despot Sekou Touré – who even had the OAU’s first SG Diallo Telli murdered in the infamous Baba Yaro prison for opposing his authoritarian rule – famously said that the “OAU was not a tribunal which could sit in judgment on any member state’s internal affairs.”

In country after country, from one dictator to another, the OAU kept quiet while African leaders butchered their own people in the name of non-interference. In cases where the OAU condoned intervention, they were not for the concepts of human rights, but rather as a pan-African philosophy to uproot colonialism, forestall foreign intervention, protect a brother African state, as a counter-intervention measure or, in case of Biafra, to protect the uti possidetis juris principle.

The Charter project was clearly under threat. Enter the President of The Gambia, Dauda Jawara.He convened two Ministerial Conferences in Banjul, The Gambia, where the draft Charter was adopted and subsequently submitted to the OAU Assembly. It is for this historic role of The Gambia that the African Charter is also referred to as the ‘Banjul Charter’. On June 27, 1981, Member States of the OAU made an undertaking to promote and safeguard freedom, justice, equality and human dignity on the continent when they adopted the Charter in Nairobi, Kenya. Five years later on 21 October 1986 (Now African Human Rights Day), after the required number of ratifications, it came into force. All the 55 AU Member States are Parties to the Charter. Article 30 of the Charter establishes the African Commission under the auspices of the African Union (AU). Article 45 of the Charter mandates the African Commission to promote and protect human and peoples’ rights in Africa.

Sector Context

The Charter sets standards and establishes the groundwork for the promotion and protection of human rights in Africa. Since its adoption 34 years ago, the Charter has formed the basis for individuals to claim rights in an international forum. The Charter also dealt a blow to state sovereignty by emphasising that human rights violations could no longer be swept under the carpet of ‘internal affairs’.

As with other regional human rights systems, the African human rights system is composed of four pillars:

(a) Norms: the treaties that enshrine particular human rights. The most important is the African Charter adopted in 1981. Other important treaties are the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights; Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (creating African Court of Justice and Human and Rights Peoples with Criminal Chamber, which has not come into force yet); the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child; the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa; and the African Charter on Democracy Elections and Governance (ACDEG)

(b) African States Parties: to the different legal instruments.

(c) Supervisory bodies which monitor, interpret, decide, and offer recommendations regarding human rights promotion and violations. The main African Union (AU) human rights supervisory bodies are the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Court) and the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (Child Committee).

(d) Non-governmental organisations, (including National Human Rights Institutions) that bring complaints, provide information, and make recommendations to the system.

Looking for a comprehensive guide as to how the system work, especially its relationship with other human rights systems around the world? We have located a fantastic ‘Guide’ that covers it all. For some of the materials, unfortunately, you may have to subscribe to them.